The US$8.5 billion critical minerals deal signed between Australia and the United States this week has placed the spotlight on how much value the Trump Administration places on securing access to these resources in its strategic contest with China. This concern has similarly influenced US agreements with Ukraine, as part of continuing US support for the war against Russia, and its interest in acquiring Greenland.

Accessing these minerals has also been a longstanding theme in the US position on deep seabed mining. This was highlighted on 24 April when President Donald Trump signed an Executive Order paving the way for the United States to commence deep seabed mining, reframing access to deep-seabed minerals as a matter of urgent national security and supply chain independence. Entitled “Unleashing America’s Critical Marine Minerals and Resources”, the Executive Order declared a national policy to bolster US leadership in deep-seabed mineral development.

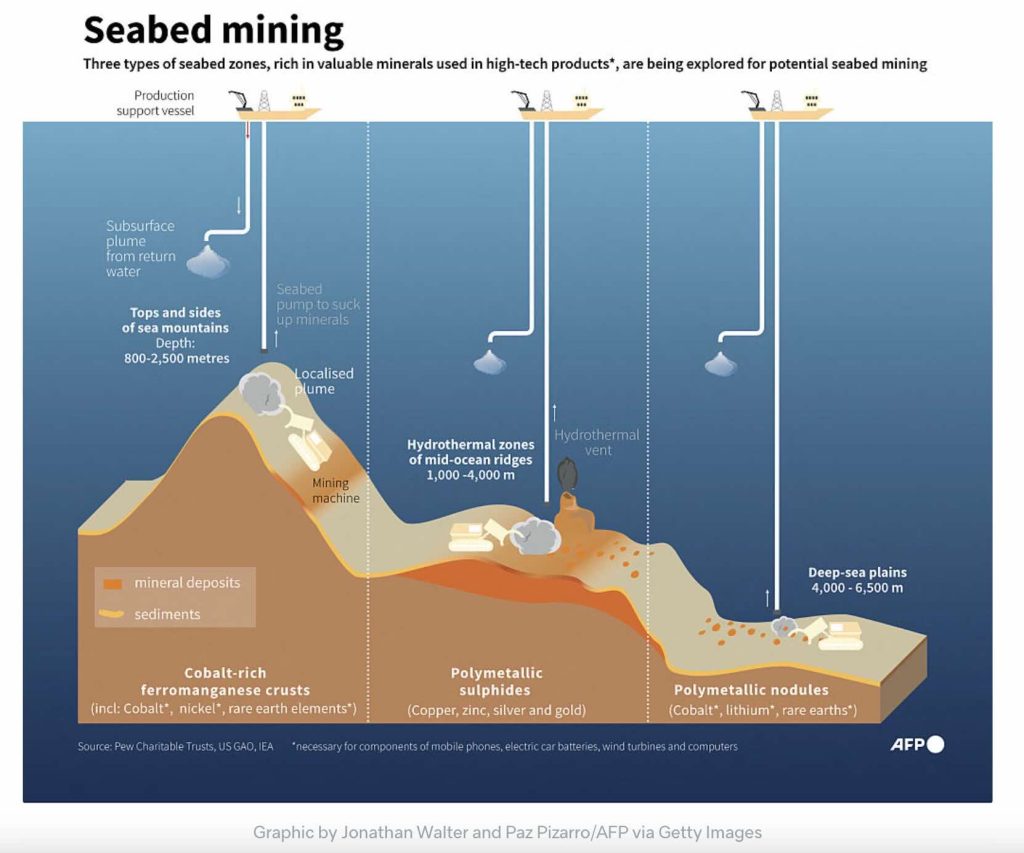

Its primary objective is clear: to secure the domestic supply of key minerals, thereby reducing economic and strategic dependence on geopolitical rivals, particularly China, which dominates global refining and processing of these same materials. Critical deep seabed minerals include manganese, nickel, cobalt, and rare earth elements.

The legal and diplomatic background here is important. During the 1970s, negotiations took place to finalise a new global oceans treaty. Central to those negotiations was development of a legal framework for deep seabed mining beyond the limits of the state-controlled continental shelf. Consensus quickly emerged that the deep seabed would not be subject to the control or ownership of any individual country and would be designated as part of the “common heritage of (hu)mankind”. Under this regime all states would enjoy equal entitlements to access and collectively enjoy the benefits of any deep seabed minerals.

The United States actively engaged in these negotiations until the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan, when it reversed its position to obtain guaranteed access to strategic minerals – such as cobalt, nickel, copper and manganese – that were considered essential for the American military industrial complex. The Reagan administration ensured that the United States became one of the handful of countries to not endorse the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). That has remained the US position to this day.

Under UNCLOS, the deep seabed and its resources are considered part of the common heritage. No country may claim sovereignty or exercise sovereign rights over deep seabed resources, and all activities conducted there must be carried out for the benefit of humankind as a whole. To operationalise this principle, UNCLOS established the International Seabed Authority (ISA). The ISA has the job of regulating all deep seabed mining activities beyond the continental shelf in accordance with the common heritage principle, including overseeing mechanisms for equitable benefit-sharing.

While the ISA has operated without major setbacks since becoming fully operational in 1996, the ISA Council has recently been undertaking a lengthy process to complete the adoption of rules, regulations, and procedures under a Mining Code that would eventually facilitate deep seabed mining. Throughout 2025, line-by-line negotiations to conclude draft exploitation regulations have proceeded. However, despite this procedural progress, fundamental disagreements persisted in key areas, including financial models for equitable benefit sharing, environmental oversight mechanisms, and liability regimes.

These delays have been further exacerbated by the parallel growth of a moratorium movement. About 30 ISA member states – supported by a significant segment of the scientific community and civil society – are advocating for a precautionary pause or outright ban on deep seabed mining. That position reflects persistent scientific uncertainty about the cumulative and potentially irreversible impacts of mining on fragile deep-sea ecosystems.

While the United States has never formally adopted UNCLOS, it has traditionally been regarded as a state that largely adheres to many key UNCLOS principles and norms. However, Trump’s 2025 Executive Order mandated the acceleration of granting permits for US entities operating in the US continental shelf and in the deep seabed area by invoking the largely dormant Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act (DSHMRA) of 1980. This domestic legislation allows the United States to issue licences for exploration and recovery in areas beyond the US claimed continental shelf and into the deep seabed, effectively creating a unilateral US regulatory structure to that administered by the ISA.

The immediate fallout from the new US approach to mining exploitation in the deep seabed has initiated a profound geopolitical and legal confrontation that fundamentally threatens the integrity of the law of the sea and deep seabed common heritage regime. The Metals Company (TMC) USA, a subsidiary of one of the most advanced deep seabed mining firms in the world, has announced its formal application for a commercial recovery permit under the US legal framework promoted by Trump’s Executive Order. This prompted a response, including by China and the European Union, openly criticising the US policy as violating UNCLOS. The ISA Secretary-General issued a firm rebuke, stating that any unilateral application of domestic law to deep seabed mining is a violation of international law and the spirit of UNCLOS.

These developments confirm that ocean governance has reached a critical inflection point. While the ISA continues to negotiate the finalisation of the Mining Code to fulfil its mandate, the United States appears determined to pursue the exploitation of deep seabed minerals outside of the accepted UNCLOS legal framework. The ISA now faces the dual challenge of finalising a robust, environmentally sound, and economically equitable Mining Code to restore its authority, while at the same time preventing the fragmentation of ocean governance. If powerful states persist in prioritising national interests over multilateral cooperation, the vision of the deep seabed as a resource for all humankind risks being irreversibly lost to a new era of resource competition.